By Donna Anderson

Yesterday marked the 136th anniversary of the worst mine disaster in Golden’s history: The White Ash Mine disaster.

Part 2. Disaster Strikes

On 9 September 1889, at about 4:00 p.m. after the evening shift had gone down to work in the active level (720 feet) of the White Ash Mine, Charles Hoagland, mine engineer, reported:

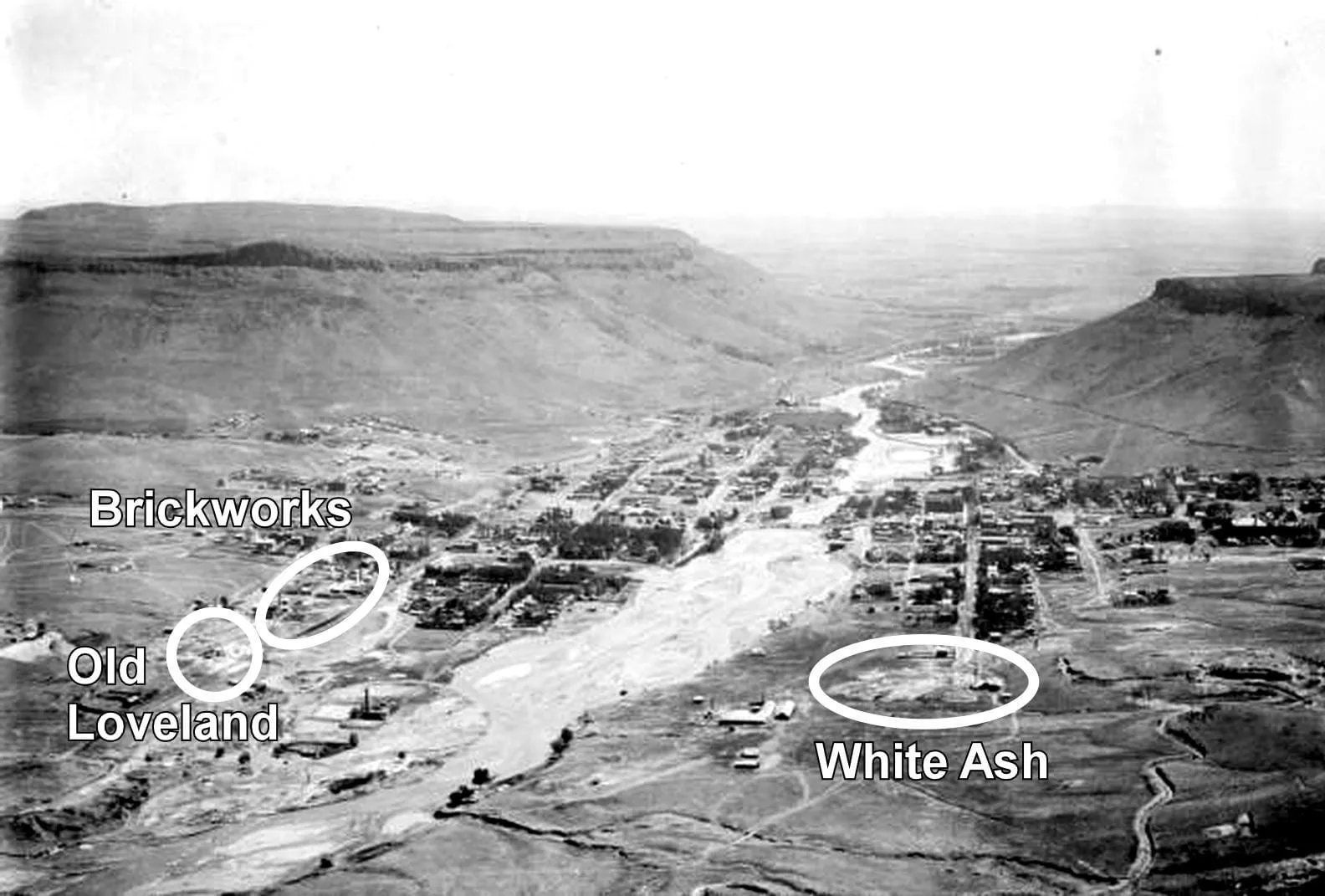

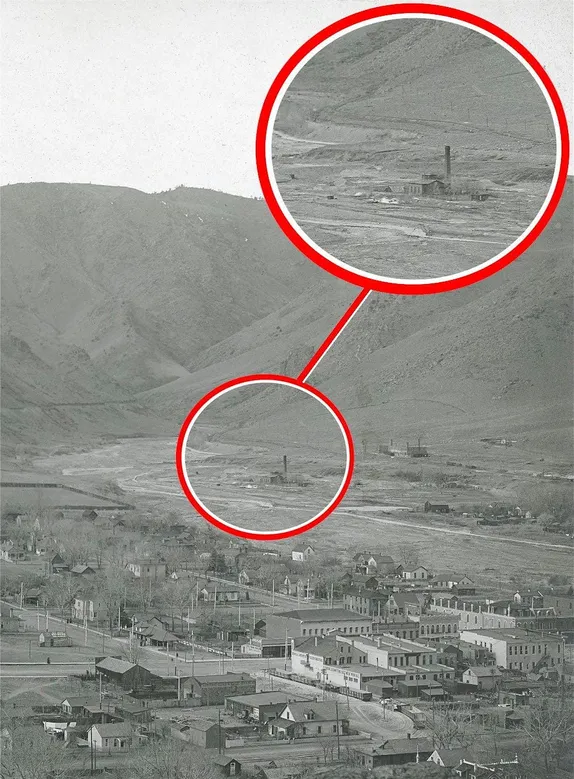

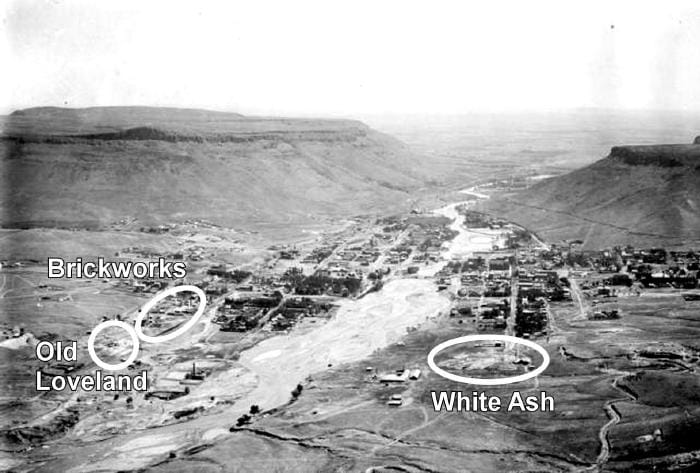

The men below sent up a signal to send down the cage. It was at once lowered. It went to within about 6 feet of the bottom of the [vertical] shaft and then struck something…We worked with the cage for a few minutes, and finally something below broke. Since then we have heard nothing…[The foreman, Evan Jones] went down on a ladder to the 280-foot level and came back…the air was so bad he had to ascend…[The men] went over to the old [abandoned Loveland] mine [located 1960 feet to the north across Clear Creek] at 6 [p.m.] and found that shaft to be perfectly dry. [It was always filled with water, used at the Golden Brick Co.].

People gathered at the mine throughout the evening and night, crazy with grief. Inspector McNeil was called at 9 p.m. When McNeil arrived at midnight, the shaft was full of carbon dioxide and the top of water was 100 feet above the bottom of the shaft. By 8:00 a.m. McNeil and mine foreman Evan Jones were able to go down the shaft in a bucket to the 480-ft level [those two gentlemen had guts], where they could hear water running. On the way they also encountered intense heat and could see timbers on fire at the 280-ft level. Within days, the mine workings completely filled with water that could not be pumped out. All was lost.

Inspector McNeil formally determined that the rock and coal pillar separating the Old Loveland and White Ash mines, probably weakened by a coal fire, broke, allowing water to burst through the 280-ft tunnel of the White Ash Mine. The water flowed quickly across the tunnel to reach the vertical shaft and then to the very lowest 720-foot level of the White Ash Mine, drowning the miners.

Thereafter, the White Ash mine was abandoned and at one point in time was considered a cemetery. Every year on the anniversary of the disaster, Goldenites placed flowers and held a memorial at the former mine site.

On 9 September 1936, in commemoration of the lives lost in the tragedy, a monument was placed at the west end of the Mines football field above the mine tunnels. The ceremony, attended by 1000 Goldenites, was led by Mayor Bert Jones, the son of former mine foreman Evan Jones, who sought to rescue the trapped miners 47 years earlier.

A new memorial, at the site of the former mine entrance on 12th Street, was dedicated by Mayor Marv Kay on 29 October 2016.