By Tom Schweich

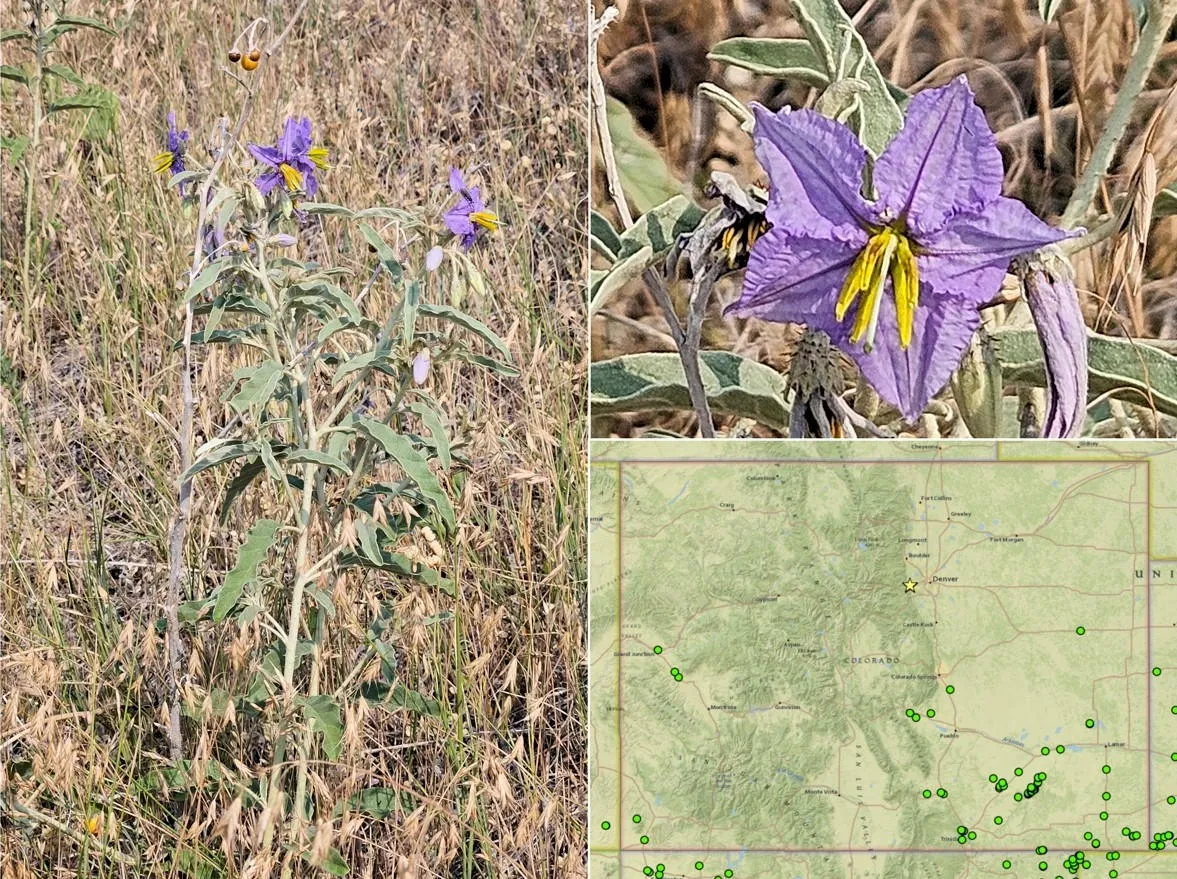

Last summer, the Weedbusters working at DeLong Park noticed a new plant. Its silvery leaves were interesting, but we had to wait until the plant bloomed to identify it. When flowers opened, their folded-back purplish petals and bright yellow anthers clearly showed it to be a nightshade. While there were several nightshades in Golden, some native and some non-native, this one was different. Eventually, we determined it to be the “Silverleaf Nightshade” — Solanum elaeagnifolium Cav.

Our plant was first described by Antonio José Cavanilles (1745 – 1804), a leading Spanish taxonomic botanist, artist and one of the most important figures in the 18th century period of Enlightenment in Spain. Cavanilles described a plant grown from seed in the Royal Botanic Garden in Madrid, Spain, writing only that the plant grows in “warm America” and was found "[On] the journey of the Spanish around the world."

The origin of the genus name Solanum is uncertain, but the species name elaeagnifolium refers to the resemblance of its leaves to those of the Elaeagnus genus, known for their silvery appearance. A familiar example is the Russian olive (Elaeagnus angustifolia L.), whose pale, shimmering leaves are a common sight in Golden. Next time you stroll along Clear Creek or drive Highway 6, look for the light-colored trees lining the trail or roadside — those are Russian olives. Unfortunately, this attractive tree is also listed as a Colorado Noxious Weed (List B), due to its invasive nature.

I had thought that DeLong Park was the only place our plant existed in Golden. Then last winter, Loraine Yeatts, a local botanist, found a large patch of silverleaf nightshade on South Table Mountain above Rimrock Drive. I went to see it last week and found a patch of 50 to 80 plants in full bloom. The large number of plants suggests it has been there for some time. The Colorado distribution of our plant is primarily southeastern Colorado, with a small cluster of collections along the Purgatoire River. How did it get to Golden? Seed could have been planted, either intentionally or accidentally or seed could have been brought in in fertilizer or soil amendment. Or possibly transported by a bird. We will probably never know.

In Colorado gardening, we often say we want to plant “natives.” But usually, we mean “native to Colorado” — a state defined by political boundaries rather than ecological ones. After all, Colorado is just a rectangle drawn across a wide range of landscapes, from the Great Plains to the Rocky Mountains. So how do we apply the concept of “native” to a specific plant? Should we keep it in Golden, or consider it non-native and remove it? And if a plant is native somewhere in Colorado but not to our local area, is it still appropriate to call it “native” in our gardens?

References

Cavavilles, Antonio Jose. 1794. Icones et descriptiones plantarum, quae aut sponte in Hispania crescunt, aut in hortis hospitantur. [Illustrations and descriptions of plants that either grow naturally in Spain or are found in gardens.] Volume 3. Madrid: Ex Regia Typographia, 1794. Description: https://bibdigital.rjb.csic.es/viewer/9681/?offset=#page=34 Illustration: https://bibdigital.rjb.csic.es/viewer/9681/?offset=#page=113